Uneven Pathways: A Comparative Study of Early Childhood Education Policies for Marginalized Communities in China and Singapore

This study compares how Singapore and China support early childhood education for marginalized groups. Despite shared goals, both face challenges that Singapore with equity gaps for low-income and minority children, and China with regional disparities and systemic barriers to access.

Both Singapore and China have undertaken major education reforms in recent decades, aiming to enhance student outcomes and build a future-ready workforce. While their policies share similar goals, they differ significantly in design and execution.

This comparative study addresses the research question: “How effective are government policies and their implementation in supporting early childhood education for marginalized communities in China and Singapore?”, the analysis is guided by Bray and Thomas’s (1995) multidimensional framework.

By analyzing how education policies impact marginalized groups, this study highlights key systemic barriers, regional disparities, and the influence of institutional structures on achieving inclusive education in the two countries of interest. Gaining insight into these challenges is crucial for guiding future policy improvements and advancing SDG4 objectives. This paper focuses on three SDG4 targets: early childhood education, equity, and student support.

Singapore’s centralized system delivers consistently high outcomes through strong governance and teacher quality. However, children from low-income, Malay, and migrant backgrounds continue to face barriers in access, participation, and parental engagement. Despite a shift toward holistic learning, the highly competitive, merit-based culture still favors more privileged families, making equity an ongoing concern.

In contrast, China’s expansive geography and centralized control result in significant regional disparities. While reforms have expanded access and improved infrastructure, implementation remains uneven especially in rural, migrant, and minority communities. Challenges such as the hukou system, underqualified rural educators, and low parental involvement hinder progress toward equitable early childhood education. Urban centers show high performance, but systemic barriers continue to obstruct nationwide inclusion.

Both Singapore and China are making education reforms to improve equity for marginalized communities. Socioeconomic pressures, cultural norms, and institutional barriers lead to uneven implementation and persistent early learning gaps. In Singapore, academic pressure benefits affluent families but limits holistic development while Malay communities face reduced access. In China, top-down policies and reforms often encounter logistical challenges and lack sufficient oversight, and when combined with systemic barriers like the household registration system that restricts access to education, they create additional obstacles for children in underserved regions from receiving equitable educational opportunities.

Singapore

Geographic and Administrative Context

Singapore is a compact city-state with a highly centralized and efficiently managed education system. Its small geographic size allows for uniform implementation of national policies and minimizes disparities in access to educational services and resources. The Ministry of Education (MOE) oversees the entire system, from preschool to tertiary education, enabling close alignment between curriculum design, teacher training, and educational outcomes.

Demographics and Marginalized Groups

Despite the universal accessibility of education, disparities persist across demographic lines. In particular, students from low-income households and specific ethnic groups, primarily Malays and some subgroups within the indegenous community, consistently underperform compared to their Chinese peers. This trend is observed even with the presence of substantial government support in the form of financial aid, targeted programs, and tuition subsidies.

According to national statistics (MOE, 2021), Singapore has approximately 170,000 children aged 0–6 years. It is estimated that around 20% of households fall into the lower-income bracket, translating to approximately 34,000 young children from disadvantaged backgrounds. A significant proportion of these children come from Malay and other indigenous families.

Singapore promotes a meritocratic education model, but systemic inequalities persist. According to MOE data (2021), Malay students continue to perform below the national average in key academic assessments. These outcomes are linked to structural socioeconomic disadvantages, including reduced access to enrichment opportunities, lower parental educational attainment, and limited cultural capital. Such disparities underscore the importance of context-sensitive strategies in closing achievement gaps.

Evolution of Singapore’s Education Philosophy

Singapore’s education system has its roots in the British colonial period, during which English schools were established to serve administrative needs. This colonial legacy persists today through the continued use of the O-Level/A-Level examination structure and a civil-service-oriented school culture. Following independence in 1965, the government recognized education as a strategic instrument for transforming a resource-scarce, young nation into a competitive global economy. A key early philosophy was survival-driven education that focused on rapid literacy acquisition, discipline, and productivity.

Over the years, Singapore’s educational philosophy has shifted from its early utilitarian roots toward a more holistic and future-oriented approach. A major turning point came in the 1990s with the launch of the Thinking Schools, Learning Nation initiative, which emphasized creativity, lifelong learning, and innovation as essential pillars of national progress. Bilingualism was formally embedded in the system to preserve cultural heritage while enhancing global competitiveness.

Education Policy Approach and Focus

Given the country's diverse population and rapidly evolving economic landscape, the Ministry of Education continuously reviews and updates the curriculum to remain responsive and relevant. Recent priorities include digital literacy, STEM education, and the cultivation of 21st-century skills such as critical thinking, adaptability, and global awareness.

While the system remains rooted in an examination-driven, meritocratic tradition, there is an increasing emphasis on differentiated learning pathways, character and values education, and the holistic well-being of students. It adopts a deliberate, evidence-informed approach to education reform. Policies such as "Teach Less, Learn More" were designed to promote deeper learning, critical thinking, and creativity over rote memorization (Singapore Ministry of Education, 2013). Reforms are typically piloted, evaluated, and refined before nationwide implementation, reflecting a strong commitment to systemic coherence.

The national curriculum framework emphasizes bilingualism, numeracy, socio-emotional development, and school readiness. Holistic child development is prioritized, with alignment across policies, curriculum, teacher training, and assessment practices.

Early Childhood Education Teacher Qualifications and Training

The country maintains high standards for early childhood educators. At minimum, teachers must hold a diploma in early childhood care and education though there is a growing emphasis on degree-level qualifications. Continuous Professional Development (CPD) is mandatory, with regular upskilling to reflect best practices and evolving pedagogical research. Class sizes are kept small, typically 12–15 children per teacher, with a student–teacher ratio of around 1:8 which enables more personalized instruction and stronger teacher-child interactions.

Access and Support for Marginalized Communities

Singapore provides robust support systems for disadvantaged families. Approximately 20% of households are considered lower-income, and a wide range of subsidies, financial aids, and developmental programs are offered to ensure equitable participation in early childhood education. Policies also encourage parental involvement, bilingual literacy, and access to anchor operators, which provide quality-assured childcare.

Nevertheless, inequalities in access remain. Lower-income families face barriers in securing places in high-quality preschools, especially those offered by private providers. Challenges include financial constraints, discrimination, academic/cognitive assessment, limited awareness of available programs, language barriers, and time limitations. To parents, financial stress can lead to challenges in affording school materials, stable housing, and conducive study environments.

While research this paper, a group of children of migrant workers or non-citizens who aren’t documented in the official MOE data but are physically present in the system, often exist on the margins that some face restricted access to public schooling or are placed in private institutions with fewer resources. These children battle with language barriers, social exclusion, and uncertain legal status, all of which can affect their ability to fully participate and thrive in school. This complex nature of education inequality in a country where the system is high-performing but still grappling with how to ensure equitable access and support for all.

Educational Outcomes

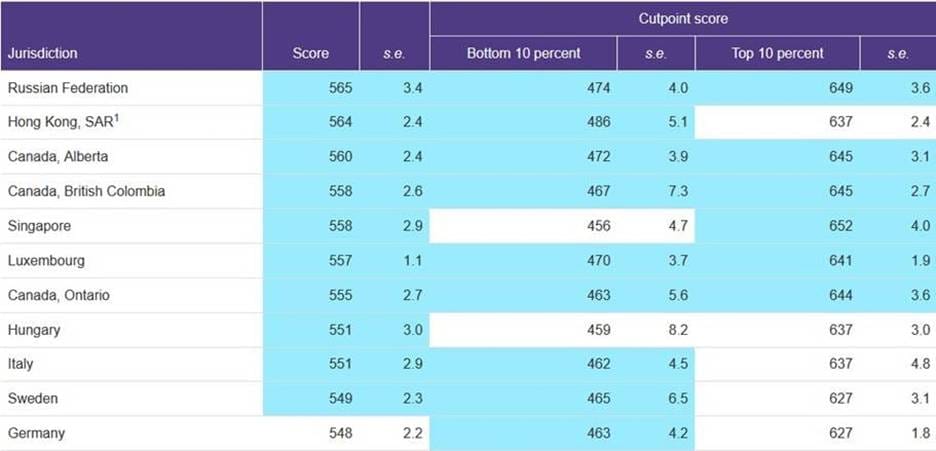

Singapore consistently ranks among the top performers in international education benchmarks. In the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), Singaporean students ranked among the highest globally in reading literacy (Mullis et al., 2017). As shown in Figure 1, average scores of fourth-grade students in Singapore achieved the highest average and cutpoint scores on PIRLS reading literacy scale among all participated counties. This outstanding result attributed to the country's strong early education foundation, quality pedagogy, and well-trained teachers.

Figure 1. Top 10 PIRLS 2016 Scores

Sustainability in Early Childhood Education in Singapore

While national policies in Singapore actively promote strong school-family partnerships, parental engagement remains uneven across socioeconomic strata, revealing a deep structural divide. Families from marginalized or working-class backgrounds often face significant obstacles to participating meaningfully in their children’s early learning. Long working hours, limited access to educational resources, and a lack of confidence or familiarity with school systems create barriers that exclude them from fully supporting their children’s development. These families often struggle to navigate a system that implicitly favors those with time, money, and social capital, resulting in unequal access to quality early childhood education. The pathway to elite primary schools, often seen as gatekeepers to future success, remains difficult to access for low-income families, who may lack the means to afford private preschool programs or prepare for competitive admissions.

In contrast, middle- and upper-income families in Singapore tend to be highly involved, often driven by anxiety over academic competition and high-stakes exams that loom even in early childhood. As a result, many parents over-invest in tuition, enrichment programs, and structured academic drilling, believing this will give their children a competitive edge. However, this misplaced focus on rote learning and academic milestones often comes at the expense of more holistic developmental goals. Singapore’s early childhood education framework emphasizes play-based learning, creativity, social-emotional growth, and inquiry-based exploration and yet these crucial aspects are frequently sidelined. Parents, in their well-intentioned efforts, may inadvertently undermine the goals of the national curriculum by prioritizing early reading, writing, and math scores over well-being and curiosity.

This dynamic not only exacerbates inequality that marginalized families are unable to engage at the same intensity but also creates a culture of stress and anxiety for both children and parents. The societal pressure to secure a place in prestigious schools fuels a competitive environment that disproportionately benefits the already advantaged. As a result, the vision of equitable and meaningful parental engagement promoted by policy is not fully realized in practice. Addressing this requires not only more inclusive outreach and support for disadvantaged families, but also a broader cultural shift toward valuing balance, emotional wellness, and diverse forms of learning in early education.

Singapore Summary

Singapore’s centralized and meticulously structured education system has led to impressive educational outcomes, yet it also highlights the challenges of achieving equity within a meritocratic framework. The country continues to refine its approach by investing in teacher quality, curriculum innovation, and support for disadvantaged groups. However, gaps in access, parental engagement, and enrichment opportunity remain areas where further improvement is needed to fulfill SDG4 to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all.

China

Geographic and Locational

China’s vast geographical expanse and diverse regional landscape pose significant challenges for uniform policy implementation. While education policies are formulated centrally by the Ministry of Education, their execution varies widely across provinces, municipalities, and districts. Urban centers like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen benefit from strong infrastructure, experienced educators, and high-performing students. In contrast, rural, western, and ethnic minority regions/provinces like Guizhou, Gansu, Xinjiang, Tibet, … etc. struggle with under-resourced schools, inadequate teacher training, and lower educational outcomes.

China’s scale introduces deep structural inequalities. These disparities significantly influence the equity and effectiveness of educational reforms, making consistent national delivery of quality education far more complex.

Demographics and Marginalized Groups

Demographic disparities in China are reinforced by the hukou (household registration) system that’s used for governing access to public services and access to education. Rural-to-urban migrants often face restricted access to public schooling in cities due to their household registration being tied to rural regions. As a result, millions of migrant children are enrolled in informal or lower-quality private schools with limited oversight.

China is home to over 100 million children aged 0–6 (NBS, 2021) and it is estimated that around 40–50%, or approximately 40–50 million, come from marginalized backgrounds. This includes left-behind children (those whose parents migrate for work), rural families, ethnic minorities, and migrant populations. These children often experience barriers to quality education, ranging from insufficient preschool access to a lack of trained bilingual teachers and culturally relevant materials.

Ethnic minorities, particularly in Tibet and Xinjiang, face systemic challenges. Many schools in these regions lack adequate infrastructure and qualified bilingual teachers. Cultural discrimination, language barriers, and a shortage of local-language materials hinder equitable learning experiences for minority students.

Evolution of China’s Education Philosophy

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, education has played a central role in the country’s political, economic, and social transformation. Initially, the education system was designed as an ideological tool to instill socialist values and support national reconstruction. In the early decades, particularly during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), academic rigor was de-emphasized in favor of political indoctrination, and many schools and universities were shut down or repurposed. However, with the advent of economic reforms in the late 1970s, China began to shift toward a more pragmatic and modernization-focused approach to education. The reintroduction of the Gaokao, national college entrance examination, in 1977 marked a major turning point, restoring meritocracy and academic competitiveness.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, China invested heavily in expanding access to basic education, promoting nine years of compulsory schooling, and rebuilding its higher education system. By the early 2000s, the focus had shifted toward quality improvement, research output, and internationalization. Initiatives like Project 211 and Project 985 were designed to fast track Chinese universities and to prepare students to catch up to those attending top universities around the around. In recent years, the Chinese government has initiated programs to reform its education system to reduce regional disparities, ease exam pressure, and encourage creativity and innovation. However, these new initiatives have yet to proven they're effectiveness and it's too early to see their long-term effect. Meanwhile, the system remains centrally managed and highly competitive, especially at the secondary and tertiary levels, where the Gaokao still determines much of a student’s academic and career trajectory.

Education Policy Approach and Focus

China’s approach to education reform has been bold and expansive, often characterized by a top-down model in which sweeping national directives are issued by the central government. While the Ministry of Education establishes broad policy objectives, the responsibility for carrying them out typically falls to provincial and local authorities. This decentralized implementation results in considerable variation in how reforms are interpreted and executed across regions.

In recent years, these reforms have increasingly reflected China’s shifting priorities. A notable example is the introduction of the “Double Reduction” policy in 2021, which was designed to alleviate academic pressure on students by reducing homework loads and curbing the rapidly growing private tutoring sector. This move aimed to address widespread concerns (Xue, Eryong, & Li, Jian 2023) about student stress and deepening educational inequality, particularly in urban areas. Another major initiative, the “Plan for Preschool Education Development (2010–2020)”, laid the groundwork for expanding access to early childhood education, especially in rural and underserved communities. The long-term vision of this plan, as extended in subsequent updates, is to achieve near-universal access to quality preschool education by 2035.

Despite these significant strides in expanding access, the quality and consistency of implementation remain key challenges. In many under-resourced areas, reforms face logistical and financial hurdles, and without adequate oversight or support, their impact can be uneven. The result is a landscape where policy ambitions are high, but educational outcomes vary greatly depending on local capacity and context.

Early Childhood Education Teacher Qualification and Training

Teacher quality in China varies sharply by region. Urban preschools often employ educators with formal degrees in early childhood education and provide professional development. In contrast, rural preschools frequently suffer from a shortage of qualified teachers, with many educators lacking even basic training in early childhood pedagogy. (Wu & Huang 2024)

Rural teachers receive fewer training opportunities, and career development pathways are limited, contributing to high turnover and low morale. This disparity in teacher preparation exacerbates educational inequalities between urban and rural children.

Access and Support for Marginalized Communities

China has made significant investments in expanding early childhood education infrastructure in recent decades, with the number of kindergartens increasing from approximately 180,000 in 2010 to over 290,000 by 2020 (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China [MOE], 2021). However, access remains highly unequal, particularly for children in rural and underserved regions. National statistics reveal that while the gross enrollment rate in preschool education reached over 85% by 2020, the quality and availability of services vary sharply between urban and rural areas. Marginalized children in remote villages often attend overcrowded preschools with inadequate facilities, outdated teaching materials, and underqualified staff. In many rural classrooms, sizes exceed 30 students, and student–teacher ratios can reach 1:20 or higher, compared to 1:11 in more affluent urban settings (Hu et al., 2014). This imbalance limits opportunities for individualized instruction and significantly hinders cognitive and socio-emotional development during critical early years.

Although government initiatives such as mobile teaching units in rural locations, implementation is inconsistent across provinces. For example, a 2018 study by China’s Ministry of Education MOE (2018) found that only 57% of rural kindergartens met national standards for physical infrastructure, and fewer than 40% had access to trained early childhood education teachers. These disparities reflect broader structural challenges, including regional funding inequities, urban-rural migration patterns, and limited oversight in resource allocation. Without more sustained and equitable investment, children in China’s rural communities remain at a disadvantage before they even enter primary school.

Educational Outcomes

China performs strongly in international assessments overall, particularly in math and science. However, these high scores are typically driven by urban pilot regions such as Shanghai and Beijing, which are not representative of national averages.

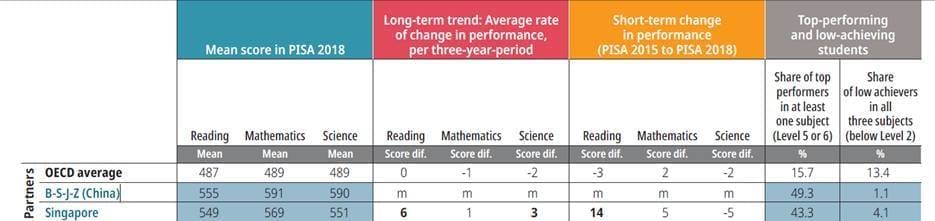

While China does not participate in Progress in the PIRLS reports, OECD (2022) Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) has included China’s urban and economically developed regions, such as Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang. As shown in Figure 2 below, these regions in China have consistently demonstrated high performance in PISA assessments. However, this representation does not encompass the broader national context particularly the rural regions which face distinct educational challenges. Children in rural and migrant communities continue to underperform in literacy and numeracy due to limited early learning opportunities, less exposure to books, and less effective pedagogy. Teng & Wang (2024) emphasizes that performance gaps between rural and urban students remain wide, despite aggregate improvements in national data.

Figure 2. China (Beijing-Shanghai-Jiangsu-Zhejiang) and Singapore Porgramme for International student Assessment (PISA) 2018 scores

Sustainability in Early Childhood Education in China

Early childhood education is deeply influenced by socioeconomic and systemic factors in China. In urban areas, middle-class families often over-invest in enrichment classes, tutoring, and advanced academic preparation, driven by anxiety over school competition. Preschool-aged children are frequently exposed to academic content well beyond their developmental level.

In contrast, parents from rural or marginalized communities often lack the time, resources, or confidence to engage meaningfully in their children’s early learning. Factors such as limited education, long working hours, and lack of awareness about developmental needs reduce their involvement to basic caregiving.

This disparity in parental engagement contributes to unequal school readiness and perpetuates intergenerational inequality. Without culturally sensitive interventions and targeted support programs, policies that aim to increase parental involvement risk widening existing gaps rather than closing them.

Moreover, the hukou system reinforces structural inequality by limiting access to quality services for migrant families. This not only affects children's enrollment in high-quality preschools but also exacerbates the cycle of disadvantage across generations.

China Summary

China’s education system has undergone a remarkable transformation in recent decades, marked by rapid modernization and a significant expansion in access. Yet beneath these achievements lie deep-rooted inequities shaped by geography, income disparities, ethnicity, and institutional barriers. While centralized planning has enabled the rollout of sweeping reforms, their effectiveness is often curtailed by inconsistent implementation at the local level and entrenched demographic divides, particularly for children from marginalized communities.

Bridging this equity gap is essential if China is to fully realize the vision of SDG4 through investment and support to ensure the sustainability and equity of preschool services (Zhou & Jiang 2024) to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all. Achieving this will require a multifaceted approach. Strengthening teacher training programs in underdeveloped regions is critical to improving classroom quality where it is most needed. At the same time, structural barriers such as the hukou system, which limits access to public education for migrant families must be addressed to promote true educational inclusion.

Equally important is the need to enhance family engagement, especially in rural and disadvantaged areas, through culturally responsive outreach and practical support. Moreover, achieving nationwide equity in funding and regulatory oversight for early childhood education centers will be key to leveling the playing field.

Ultimately, closing the gap in early childhood education will require not only sustained public investment and thoughtful policy reform but also a commitment to empowering families and educators at the grassroots level. It is in these communities that the foundation for a more equitable and inclusive future must be built.

Sustainability Challenges in Early Childhood Education in Singapore and China

Both China and Singapore have prioritized early childhood education as essential to long-term academic and social development. Singapore’s compact size and centralized governance enable consistent implementation of national policies, ensuring quality teacher training, standardized curricula, and broad access to preschools. In contrast, China’s vast geography and socioeconomic disparities make uniform policy implementation difficult. While universal early childhood education access by 2035 is an ambitious goal, outcomes vary widely that urban regions benefit from better-trained staff and infrastructure, while rural and minority areas often lack qualified teachers and adequate oversight.

Table 1 provides a visual comparison of the education policy approaches and priorities, socio-economic contexts, estimated size of the marginalized student population, early childhood teacher qualifications and ongoing professional development, average class sizes, and academic outcomes.

Table 1: Singapore and China Early Childhood Education Comparative Table

Parental engagement in both countries reflects structural and social inequalities. Singapore actively promotes family involvement through bilingual programs, financial aid support, and community outreach. However, working-class families still face barriers like access to high quality education, time constraints, language challenges, lack of confidence, and limiting meaningful participation. In China, parental involvement in education is significantly influenced by the hukou household registration system, which restricts migrant families' access to urban public schools. When parents work in cities where their household registration does not apply, they are often unable to enroll their children in local public schools. As a result, many parents live apart from their children during critical developmental years and aren’t able to actively participate in their education and daily lives. This contributes to unequal resource distribution and limits opportunities for rural children. While urban middle-class parents often overinvest in early academics, leading to heightened stress and competition, rural and left-behind families frequently lack the knowledge and resources to support their children’s learning that exacerbates social immobility.

Despite comprehensive education policies and alignment with SDG 4.1, both countries struggle to bridge the gap between policy intent and education equity, especially in marginalized communities. Cultural pressures, institutional barriers, and socioeconomic stressors result in inconsistent or superficial engagement that reinforces early learning disparities. In Singapore, intense academic competition pushes affluent families toward excessive academic drilling, often at the expense of holistic child development. Marginalized Malay communities often don’t receive the same access available to more affluent families. Meanwhile, in China’s underserved areas, top-down policy approaches often overlook local cultural and introduce both intentional and unintentional barriers.

Policies that recognize to families’ diverse realities and respond with resources to program with accountability would help move beyond the current challenges, making education more inclusive and effective. This shift is essential to advancing SDG 4.1 and ensuring every child, regardless of background, has equitable access to high-quality early education and a strong foundation for lifelong learning.

Future Research

A deeper exploration of Singapore and China’s education structure and reforms from the standpoint of parental engagement and teacher tenure could bring new dimensions for understanding people factors in carrying out policies and long-term student success in marginalized communities.

Parental engagement remains a critical but often underexplored dimension of educational equity in early childhood settings. While governments may introduce supportive policies, meaningful involvement from families. It is frequently hindered by a combination of socioeconomic constraints, cultural mismatches, and limited awareness of their potential role in early learning. For example, migrant parents or those with lower educational attainment may feel unprepared or unwelcome in formal education spaces, leading to minimal participation in their children’s academic development. Future research could explore how culturally responsive strategies such as community-based outreach, multilingual resources, or parent education programs can be tailored to specific populations to foster more inclusive family-school partnerships. Understanding what types of engagement are most effective and sustainable could have far-reaching implications for policy design and program implementation aimed at reducing early learning disparities.

In parallel, the issue of teacher tenure and its relationship to classroom quality also warrants deeper investigation. Tenure can offer educators stability, experience, and confidence, potentially leading to stronger instructional practices and improved student outcomes. However, tenure could potentially lead to resistance to change and lack of accountability in student performance. Furthermore, disparities between tenured and non-tenured teachers in terms of training access, job security, and professional development opportunities may create inconsistencies in educational quality especially in underserved regions. Exploring how tenure status affects pedagogy, academic success, classroom management, and responsiveness to student needs could yield actionable insights for teacher policy reform. Comparative studies between China and Singapore, with their differing teacher training systems and professional hierarchies, would be particularly valuable in identifying best practices.

Future Research Questions:

1. What culturally responsive models of parental engagement are most effective in improving early childhood education outcomes for marginalized families in China and Singapore?

2. How does the tenure status of early childhood educators influence their instructional practices and the developmental progress of children in socioeconomically diverse classrooms in China and Singapore?

References

1. Bray, M., & Thomas, R. M. (1995). Levels of comparison in educational studies: Different insights from different literatures and the value of multilevel analyses. Harvard Educational Review, 65(3), 472–491.

2. Hu, Bi Ying, Zhou, Yisu, Li, Kejian; Killingsworth Roberts, Sherron Olney (2014). Examining Program Quality Disparities Between Urban and Rural Kindergartens in China: Evidence From Zhejiang. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 2014-10, Vol.28 (4), 461-483

3. MOE. (2021). Education statistics digest. Ministry of Education, Singapore. https://www.moe.gov.sg/about-us/publications/education-statistics-digest

4. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). Statistical bulletin of national education development in 2020.

5. Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2017). PIRLS 2016 international results in reading. TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College.

6. National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS). (2021). China Statistical Yearbook 2021. Beijing: China Statistics Press.

7. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2022-results-volume-i_53f23881-en.html

8. PISA 2018 results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2018-results-volume-i_5f07c754-en.html

9. PIRLS 2006 Report, https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pirls/table_1.asp

10. Singapore. Ministry of Education (2013). Engaging our learners: teach less, learn more. Ministry of Education, 77-95.

11. Teng, Y., & Wang, D. (2024). Migration for school choice: urbanisation and rural social stratification in China. Comparative Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2024.2398342

12. Wu, J., & Huang, R. (2024). Exploring beliefs among Chinese preschool teachers and their associations with perceived practices and process quality. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2024.2414907

13. Xue, Eryong, & Li, Jian (2023). What is the value essence of "double reduction" (Shuang Jian) policy in China? A policy narrative perspective. Educational philosophy and theory, 2023-06, Vol.55 (7), p.787-796

14. Zhou, J., & Jiang, Y. (2024). Sustainability of the Public–Benefit Preschool Education Service System in China: Evidence from a National Study. Early Education and Development, 36(1), 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2024.2360875